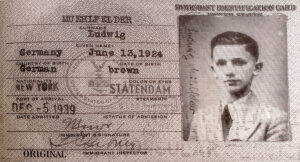

Let’s start at the beginning: Walk us through the events that led to Laemmle saving your father’s life.

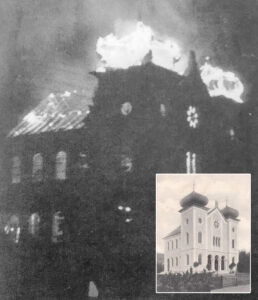

My father was born in 1924 in a town in Germany called Suhl, located in what later became East Germany. When he was 14, his father was arrested during Kristallnacht [called the ‘night of broken glass,’ which occurred on Nov. 9 and 10, 1938. On that night, Nazis in Germany arrested nearly 30,000 Jewish men age 15 and older and sent them to concentration camps, and many synagogues were destroyed across Germany]. My grandmother immediately went to the Gestapo headquarters nearby. The local Gestapo were neighbors she knew. They told her my grandfather had been taken to Buchenwald, which at that time was principally a concentration camp, not yet a death camp. My grandmother presented them with an invitation my grandparents had obtained to go to the U.S. consulate in Berlin for a visa, and so the Gestapo released my grandfather (but not before hitting him over the head for wearing a hat, which left him hard of hearing for the rest of his life). This shows how early on [before the war] this was, because that wouldn’t have been possible later.

Kristalnacht, November 9/10, 1938. The synagogue of Suhl in flames one year after Ludwig Muhlfelder became bar mitzvah there. Inset: Postcard of Suhl Synagogue in 1904

Shortly thereafter, my grandparents, my disabled aunt, and 14-year-old father went to the consulate. Because my aunt was disabled, my grandparents were presented with a choice: Either the entire family would stay in Germany, or my grandfather could go to America, get a job, and demonstrate that he could support his family and that they would not be a burden to the government. The children were excused from the conversation, and my grandparents were given 15 minutes to decide. They decided that my grandfather would go to the U.S. in the hopes of saving at least one life. He came to America in early 1939, and my grandmother and the two children were required to stay behind.

Soon after, my grandmother, father, and aunt were forced to leave their house and move into what was called a “Jew house” in the town in which my father was born. “Jew houses” were designated houses in which Jewish people were forced to live after being removed from their homes. In the meantime, Germany invaded Poland on Sept. 1, 1939, not quite a year after Kristallnacht. My father, who by then had turned 15, told my grandmother that he didn’t believe they could come to America, because by that point the English Channel was mined. However, they soon received a telegram that their visa had been granted and they could come to America. The visa was granted because Laemmle put up a million-dollar affidavit for not just my father and his family, but other families too.

Because of this visa, my father and his family were able to leave Germany and go west on the train tracks in their town to freedom. Every other Jewish person that was left behind in my father’s town was taken east on the train tracks and ultimately perished. To the best of my knowledge, my father and his family were the last Jewish people to get out.

How did Laemmle choose your father’s family as one of the many for which he wrote affidavits?

Laemmle was a distant relative, and many of the people Laemmle saved were family members. I believe my grandmother’s mother was Laemmle’s mother’s sister. They weren’t so distantly related that they had never heard of each other, but not closely related either.

What was your father’s new life in America like?

My father came to America with his family on the Statendam. He knew some English when he arrived in the U.S. because my grandmother had hired an English tutor for him in Germany. He went to high school, but he couldn’t be drafted [to fight in World War II] because he was not yet a United States citizen. But he volunteered to be drafted and eventually fought in the Battle of the Bulge under [Lt. Gen. George S. Patton Jr.’s] Third Army, and survived that too. He told a lot of stories about how the American Army used his proficiency in German to their advantage.

After the war, he went to college on the G.I. Bill at the Newark College of Engineering [now known as NJIT], and then got his master’s degree in electrical engineering. He later became an aeronautical engineer with 16 patents, of which he was extraordinarily proud. Most of his patents have to do with controlling the attitude and propulsion of satellites from Earth. He was elected as a member of AIAA [the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], a distinguished achievement.

Did your father maintain a connection with Laemmle after he saved his life?

I don’t know if my father ever tried to contact Laemmle, but my father spoke frequently about Laemmle when I was a child. I believe the affidavit Laemmle put up for my father and his family was the last affidavit Laemmle wrote. Laemmle died Sept. 24, 1939, before my father came to America.

Knowing you owe your existence to someone is something that walks with you throughout every step of your life’s journey. How did Laemmle’s heroism shape the path your father took after he was saved? In what ways did your father dedicate his life to remembering Laemmle and what he did for him?

For the rest of his life, my father was profoundly grateful that he had been spared. He often walked around the property where I grew up and said, ‘I live like a king.’ He turned the property into an orchard of fruit trees, which reflected his celebration and appreciation of life. He was a magnificent person of incredible integrity and backbone who dedicated his life to remembering, not forgetting, those who perished in the Holocaust.

He was active in his synagogue and served as president. In 2000, he published an autobiography called Because I Survived, in which he wrote about Laemmle. When the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, my dad was invited to what he later referred to as the ‘town of his birth,’ not his ‘hometown.’ Although he didn’t have any desire to return to Germany, when he published his book he started to be contacted by people whom he had known in school. So, he accepted their invitation to return and speak publicly and at the local schools in an effort to learn from the past. He also conducted a reading at a local bookstore, which was filled with people who were emerging from the Cold War and were starved for information about the Holocaust. They had received only limited and distorted information about the Holocaust during the period of Soviet domination. People were eager to learn what actually happened.

My father also spoke at Lafayette three times. The last time was in 2003, after he had a stroke and was dying. Kirby 104 was overflowing with attendees. It was sheer determination and will on his part to speak one more time. He was committed to educating and inspiring people to speak up in the face of inhumanity.

Now let’s fast-forward: How did you connect with Freedman while he was creating Carl Laemmle?

When Freedman decided to make the movie, he started doing research. Because Laemmle’s name is mentioned in my father’s book, Freedman Googled my father’s name and found a YouTube video of an interview that was done at Lafayette about my dad. I remember being in my office when my phone rang, and it was Freedman. He said, ‘Does the name Carl Laemmle mean anything to you?’ It sent shivers down my spine. Although my father had been gone for more than a decade, learning that Freedman was creating this fitting tribute to Laemmle left me with a deep sense of gratitude. It would have pleased my father greatly. In response to Freedman’s request, I collected photographs and shared everything I knew about Laemmle that my father had told me so he could use it in the film.

How did you feel about the film when you first saw it?

My family was invited to the preview in New York, and the room was filled with descendants of Laemmle’s humanitarian efforts. Most of the people in the room were [Holocaust] survivors or descendants of survivors. You couldn’t help but think of those who would have been descendants of those who didn’t survive. It was a powerful experience.

Laemmle directly saved hundreds of families, and so many lives came to be because he saved the people he did. The humanity Laemmle exhibited inspires all of us, and I’m pleased that Freedman told his story because it’s so exceptional. If the film inspires someone to do good, it will have both preserved history and influenced the future.

Why was it important to you that the Lafayette community saw this film?

My father used to quote George Santayana, a famous philosopher, who said, ‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.’ He believed in learning from the past, and one person can and does make a difference. Like Laemmle, my father dedicated his life to not forgetting. I feel it’s my responsibility to continue to tell the story, and help people not forget and to learn from the past. For me, showing the film at the College was an important opportunity to do that and honor what my father felt so strongly about.

Many people I worked with over the years had known this was a defining part of my life. Former provost June Schluter edited my father’s autobiography, and Diane Shaw, director emeritus of special collections and College archives, had mounted a museum exhibit at the College in 2006 in honor of his life. After the screening, a few colleagues told me they didn’t know this part of my family’s history. I hadn’t realized that with the passage of time, many people who are newer colleagues don’t know my family’s story. It made me realize that memory is brief, and that’s why continuing to remember is so vital.

What’s the most important lesson we can learn from Laemmle’s story?

Laemmle had great glory and acclaim in the movie industry, and he had every reason to just bask in his success. But he never forgot his humanity. The courage, follow-through, and determination he evidenced was inspirational. He retained lawyers, lobbied the State Department, and wrote affidavits until he died—and did all that while at the height of his professional career. He responded to the great calling to save lives and was indefatigable.

In the Talmud [the book of Jewish law], it says ‘Whoever saves a single life, it is considered as though they saved an entire world.’ The fact that one can make a difference with one’s life is what Laemmle’s work powerfully demonstrates. He reminds us that we’re not relieved from the obligation to repair the world because we’re busy with our other responsibilities. He reminds us to look for opportunities to act courageously.

Many know Laemmle for his work in the film industry and his list of successful films, but what does this man mean to you?

I owe my life to him. Had he not put up that affidavit, my father wouldn’t have made it. Carl Laemmle is a modern-day hero.